I DT_NEEDED HELP !

This blog post will explain what I've learned about ELF dynamic entries and how they may be obfuscated on Android.

Introduction

Last winter, I wanted to hook into an Android application for a project at work. The primary objective was to bypass the anti-hooking techniques and intercept the data exchanged between a drone and its controlling application prior to a firmware analysis. Long story short, after multiple unsuccessful attempts I set this project aside but it never really left my mind.

Fast forward 10 months later, I came across an article that I missed from Nozomi Networks Labs.

Not only did this article surprise me—it had already done all the research more than a year earlier—but it also managed to hook the packing library and dump the DEX files using the exact same techniques I had tried.

This blog is a retro-analysis on how they did it and what I missed during my initial attempts.

Btw, I am a rookie. There are a lot of mistakes and imprecisions in this article.

Presentation of the Problem

Prior work

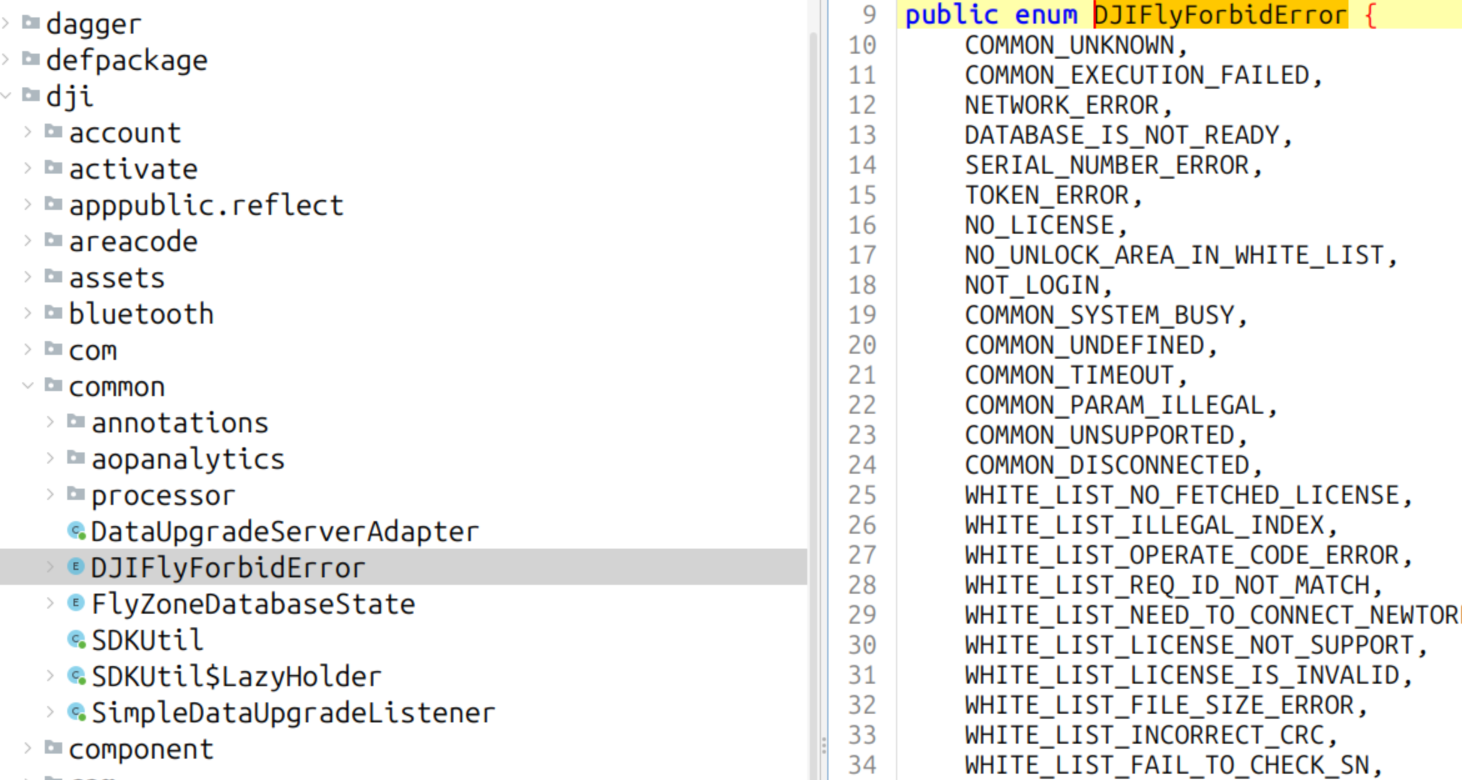

The DJI Fly (“dji.go.v5”) should not be misunconfused with the DJI Pilot application. The latter — specifically its packing mechanisms — has already been reverse engineered multiple times by both Synacktiv and Quarkslab. I highly recommend that you read Eric Le Guevel’s article the ART of obfuscation on which I based my research.

From what I have read, the DJI Pilot APK is protected by the SecNeo/BangCle wrapper and its protection scheme consists in splitting the classes in multiple encrypted DEX files.

Dumping the DEX files dynamically seemed pretty straightforward: Hook the decryption function decrypt_jar_128K from the libDexHelper.so native library and dump the memory. A less trivial approach would consist in reversing the encryption mechanisms and rebuilding the DEX files locally.

Note: in DJI Fly, past 1.12 ~ 1.13 the libDexHelper.so app was renamed libAppGuard.so. But it uses the same code base.

Since both apps are packed using the same packer, all I have to do was to reproduce theses steps. Easy ..right?

(Pic not related)

Well obviously not, otherwise this article wouldn’t exist.

- First of all, the

decrypt_jar_128Kmethod does not exist in DJI Fly. So I can’t unpack it statically. - Secondly, the DJI Fly unpacking lib comes with some heavily obfuscated anti-frida techniques.

From a static (and painful) analysis, I believe that the anti-frida code is triggered before the hidden classes are loaded. So we will need to bypass these anti-debugging techniques before dumping the dex files.

Attempts and Failures

Among the existing methods, I tried to inject a frida-gadget into the unpacking binary. For that, I used LIEF, more specifically their own tutorial to inject a frida gadget into a native lib.

This technique did not work, and the app no longer booted. To ensure this was not due to the injected gadget, I simply read and saved the program using LIEF—without editing the PT_DYNAMIC table (I will explain this concept further down in this article)—and got the same results. (Spoiler: I was two times wrong)

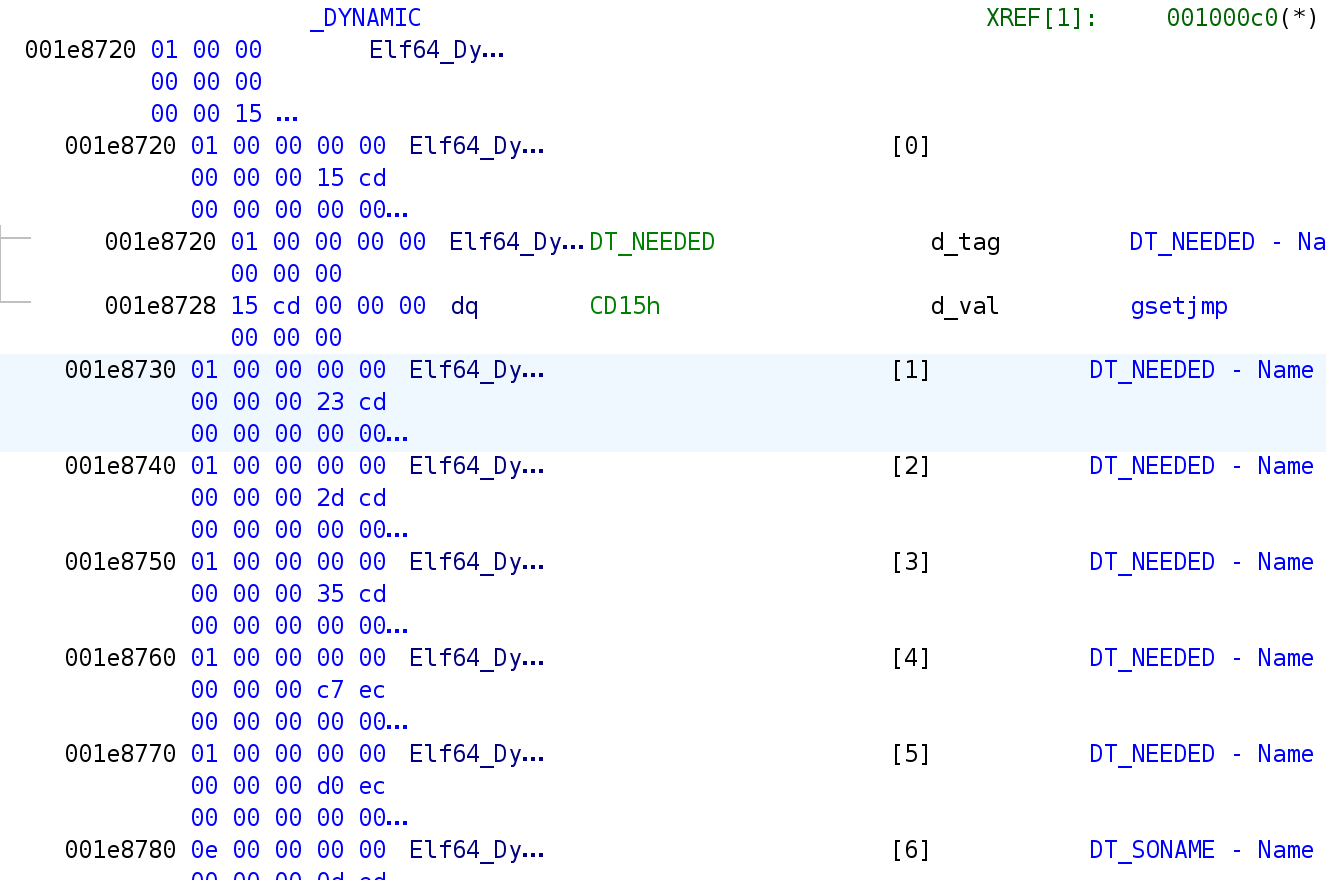

Is displayed below the PT_DYNAMIC table of the libAppGuard.so file before injection :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

➜ readelf -d libAppGuard.so

readelf: Error: no .dynamic section in the dynamic segment

Dynamic section at offset 0xefb90 contains 8 entries:

Tag Type Name/Value

0x00000001 (NEEDED) 0xcd15

0x00000001 (NEEDED) 0xcd23

0x00000001 (NEEDED) 0xcd2d

0x00000001 (NEEDED) 0xcd35

0x00000001 (NEEDED) 0xecc7

0x00000001 (NEEDED) 0xecd0

0x0000000e (SONAME) 0xed0d

0x00000000 (NULL) 0x0

And after injection:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

➜ readelf -d libAppGuard.so.out

readelf: Warning: Section 0 has an out of range sh_link value of 118202

readelf: Error: no .dynamic section in the dynamic segment

Dynamic section at offset 0xefb90 contains 33 entries:

Tag Type Name/Value

0x00000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libapagnan.so]

0x00000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libandroid.so]

0x00000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [liblog.so]

0x00000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libz.so]

0x00000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libm.so]

0x00000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libdl.so]

0x00000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libc.so]

0x0000000e (SONAME) Library soname: [libAppGuard.so]

0x00000019 (INIT_ARRAY) 0xe5240

0x0000001b (INIT_ARRAYSZ) 8 (bytes)

0x0000001a (FINI_ARRAY) 0xe5248

0x0000001c (FINI_ARRAYSZ) 16 (bytes)

0x00000004 (HASH) 0x228

0x6ffffef5 (GNU_HASH) 0x29f8

0x00000005 (STRTAB) 0xe098

0x00000006 (SYMTAB) 0x52a8

0x0000000a (STRSZ) 60705 (bytes)

0x0000000b (SYMENT) 24 (bytes)

0x00000003 (PLTGOT) 0xe8950

0x00000002 (PLTRELSZ) 14352 (bytes)

0x00000014 (PLTREL) RELA

0x00000017 (JMPREL) 0x27888

0x00000007 (RELA) 0x1d9d0

0x00000008 (RELASZ) 40632 (bytes)

0x00000009 (RELAENT) 24 (bytes)

0x0000001e (FLAGS) BIND_NOW

0x6ffffffb (FLAGS_1) Flags: NOW

0x6ffffffe (VERNEED) 0x1d990

0x6fffffff (VERNEEDNUM) 2

0x6ffffff0 (VERSYM) 0x1cdba

0x6ffffff9 (RELACOUNT) 1093

0x0000000c (INIT) 0x108098

0x00000000 (NULL) 0x0

Weird isn’t it ? Where do these entries come from ? But it’s not everything. If you open the injected binary using Ghdira, you may see the following dynamic table:

In Ghidra, the dynamic table has scrambled strings. WTF ?

Note: prior to injection in Ghidra, the dynamic table would look like the libAppGuard.so.out shown above, minus the libapagnan.so.

Many Questions

You may be asking yourself:

- Why can’t

readelffind the.dynamicsection? - After injection, why does

Ghidrashow 6DT_NEEDEDtags butreadelfshows 7 ? - Why does

readelfshow integers instead of names before the injection, but not after? - Why does

Ghidrashow incorrect lib names after the injection, but not before? (not shown in the screenshots) - In

readelfafter injection, where do all these new dynamic entries come from?

Rookie me from 2024 gave up on this for multiple (very) good reasons. But I kept it as a side project for when I have more time or feel better prepared.

Answering these questions will be the red line of this article. Once we’ve understood this, we should be able to inject our code and dump these dex files.

Turning point

As said earlier, I set this project aside. And that’s how it went until I found this blogpost from Nozomi Networks Labs. Not only did they managed to hook and dump the DEX files, but they did it using the exact same* method I had tried.

“We dump the decrypted .DEX files by reading the raw memory layout of the application from /proc/self/maps through a code injection, exploiting DT_NEEDED entries with LIEF from QuarksLab, and inspecting it to extract the unpacked data.”

* Actually ☝️🤓, they used the same technique but did not injected any

frida-agent(from what I’ve understood). Moreover, they never say which lib they injected.

Unfortunately, their article does not provide more information on how they achieved it. But at least now, I have proof of the feasibility of this technique, and all I have to do now is try harder™.

Anatomy of a Fail

So, what did I miss? If you want the short answer, jump straight to the conclusion. Otherwise, stay with me as I will first explain the concepts required to fully understand the answer.

The ELF File Format

ELF Structure

In Linux, at the beginning of each executable, there is an ELF (Extensible Linking Format) file structure that starts with 7F 45 4c 46 or 0x7F ELF.

In the ELF structure you may find information regarding the segments and sections tables.

A segment is the logical representation of a file in memory. A program header is an entry that describes a segment. You will often see these words used interchangeably.

The ELF structure is described below. I won’t go into much detail as it’s already well documented online.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

typedef struct {

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT];

Elf64_Half e_type;

Elf64_Half e_machine;

Elf64_Word e_version;

Elf64_Addr e_entry; <- Entry point

Elf64_Off e_phoff; <- offset of PH

Elf64_Off e_shoff; <- offset of SH

Elf64_Word e_flags;

Elf64_Half e_ehsize;

Elf64_Half e_phentsize; <- size of a PH entry

Elf64_Half e_phnum; <- number of PH entries

Elf64_Half e_shentsize; <- size of a SH entry

Elf64_Half e_shnum; <- number of SH entries

Elf64_Half e_shstrndx;

} Elf64_Ehdr;

At this point, remember that this structure describes the offset, size and number of entries of the segment ELF64_Phdr[] and section Elf64_Shdr[] tables and that these information are processed by the linker when loading the ELF file.

We will now clarify what are segments and sections.

Segments

Program headers (segments) describe how the operating system should load and map parts of an executable into memory.

⚠️ Segments are required for the binary to run.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

typedef struct {

Elf64_Word p_type; <- Type of the Program Header

Elf64_Word p_flags;

Elf64_Off p_offset; <- Offset in the file

Elf64_Addr p_vaddr; <- Address in memory

Elf64_Addr p_paddr;

Elf64_Xword p_filesz;

Elf64_Xword p_memsz;

Elf64_Xword p_align;

} Elf64_Phdr;

The Dynamic Segment:

In the program header table, there should be exactly one entry of type PT_DYNAMIC. This entry is used by the linker to find the position of the dynamic table as pointed by the p_vaddr attribute.

Sections

Sections define the logical organization of the executable’s contents, like code, data, or symbols, for the linker and loader. Sections provide useful data for static analysis or debugging.

⚠️ Sections are usually not required for runtime.

As a result, a program only needs the segments to be valid in order to be executed properly. Sections can be stripped from the file or deliberately corrupted to complicate reverse engineering..

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

typedef struct {

Elf64_Word sh_name;

Elf64_Word sh_type;

Elf64_Xword sh_flags;

Elf64_Addr sh_addr;

Elf64_Off sh_offset;

Elf64_Xword sh_size;

Elf64_Word sh_link;

Elf64_Word sh_info;

Elf64_Xword sh_addralign;

Elf64_Xword sh_entsize;

} Elf64_Shdr;

The Dynamic Section: (aka The Dynamic Table)

The dynamic section is the dynamic table.

The dynamic section must be pointed by the PT_DYNAMIC header of the process header table.

The dynamic section can be pointed by the SHT_DYNAMIC entry of the section table.

Actually ☝️🤓,

.dynamicis the canonical name of the ELF section that holds the dynamic table.SHT_DYNAMICis the type of.dynamicsection. The same goes for thePT_DYNAMICwhich is the type of the dynamic segment.

In other words, both the dynamic section and the dynamic segment should reference the same table. But you must not trust the section table.

The dynamic table in itself is a data structure used to manage the dynamic linking of a binary file upon loading.

It contains useful information such as (but not limited to):

- The entry point that gets executed before the actual entry of a binary.

- The list of dependencies that must be loaded before the binary is run.

In our case, we want to add a dependency (that we control) in the dynamic table in order to inject code as the target application.

The structure of a dynamic table entry is shown below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

typedef struct {

Elf64_Sxword d_tag; // type (DT_NEEDED, DT_INIT, etc.)

union {

Elf64_Xword d_val;

Elf64_Addr d_ptr;

} d_un;

} Elf64_Dyn;

In order to know which entry corresponds to what, Dynamic Array Tags or d_tags. Some entry with specific tags are required, some are optional.

Is presented below the extract of only the required entries in a dynamic table of a shared object :

| Name | Value | d_un | Executable | Shared Object |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT_NULL | 0 | ignored | mandatory | mandatory |

| DT_NEEDED | 1 | d_val | optional | optional |

| DT_HASH | 4 | d_ptr | mandatory | mandatory |

| DT_STRTAB | 5 | d_ptr | mandatory | mandatory |

| DT_SYMTAB | 6 | d_ptr | mandatory | mandatory |

| DT_STRSZ | 10 | d_val | mandatory | mandatory |

| DT_SYMENT | 11 | d_val | mandatory | mandatory |

Notice that I left one optionnal entry: DT_NEEDED

If you are interested to know more about this topic, I recommend you this reading.

Overall representation

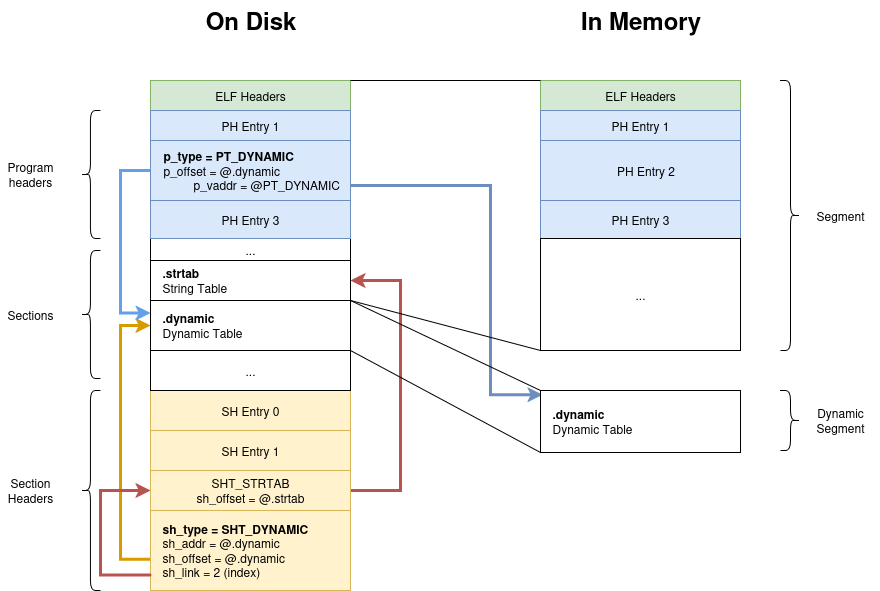

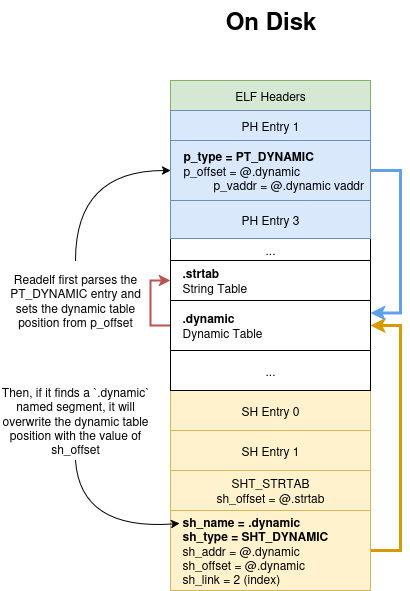

To help you figure out how this works, here is a representation of what a common binary should look like on disk and in memory. You may observe the program headers, segments, section headers and sections and which points to what.

As you can see, both SHT_DYNAMIC and PT_DYNAMIC entries point to the .dynamic section which holds the dynamic table.

Notice that the

PT_DYNAMICentry points two times to the dynamic table : Once on disk (p_offset) and once in memory (p_vaddr).

Loading and Linking Processes

When you double click on an ELF file, the program does not magically appear in memory, ready to run. The Linux kernel is responsible for handling your request, loading the process into memory, and preparing it to run.

To understand how launches a process is launched, read this article.

Here is a (very simplified) TLDR:

- The loader reads the Program Header Table (PHT) for

PT_LOADentries to map the program in memory. - The linker then reads the

p_vaddrvalue of thePT_DYNAMICentry to find the virtual address of the Dynamic Table. - The linker does more stuff we won’t talk about here

Readelf Internals

As the good IT engineer you are, you did read the man page of the readelf program. Right?

1

2

3

-d

--dynamic

Displays the contents of the file's dynamic section, if it has one.

As you may have heard, sections should not be trusted. So why doesn’t the program uses the dynamic table via the process headers (PT_DYNAMIC) instead? The answer is obviously more nuanced than this.

The next chapter will walk you through how readelf finds and parses the dynamic table.

How does readelf find the dynamic table?

Here is how the function process_program_headers() finds the dynamic table:

- Sets the address of the dynamic section by reading

p_offsetof the program headerPT_DYNAMICentry. - If there is a

.dynamicsection, it replaces the address of the dynamic section by the value of thesh_offsetattribute of theSHT_DYNAMICentry.

You may find below the source code of the “process_program_headers” of the readelf executable.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

static void process_program_headers(Filedata * filedata)

{

Elf_Internal_Phdr * segment;

//[some code]

for (i = 0, segment = filedata->program_headers;

i < filedata->file_header.e_phnum;

i++, segment++)

{

if (do_segments){

switch (segment->p_type)

{

//[SOME CODE]

case PT_DYNAMIC:

if (dynamic_addr){

error (_("more than one dynamic segment\n"));

/* By default, assume that the .dynamic section is the first

section in the DYNAMIC segment. */

dynamic_addr = segment->p_offset;

dynamic_size = segment->p_filesz;

/* Try to locate the .dynamic section. If there is

a section header table, we can easily locate it. */

if (filedata->section_headers != NULL)

{

Elf_Internal_Shdr * sec;

sec = find_section (filedata, ".dynamic");

if (sec == NULL || sec->sh_size == 0)

{

/* A corresponding .dynamic section is expected, but on

IA-64/OpenVMS it is OK for it to be missing. */

if (!is_ia64_vms (filedata))

error (_("no .dynamic section in the dynamic segment\n"));

break;

}

dynamic_addr = sec->sh_offset;

dynamic_size = sec->sh_size;

/* The PT_DYNAMIC segment, which is used by the run-time

loader, should exactly match the .dynamic section. */

if (do_checks

&& (dynamic_addr != segment->p_offset

|| dynamic_size != segment->p_filesz))

warn (_("the .dynamic section is not the same as the dynamic segment\n"));

}

break;

}

}

}

}

}

How does readelf finds sections?

It’s as simple as looping through the sections and checking the name.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

static Elf_Internal_Shdr *find_section (Filedata * filedata, const char * name)

{

unsigned int i;

if (filedata->section_headers == NULL)

return NULL;

// Loops through section headers

for (i = 0; i < filedata->file_header.e_shnum; i++)

// If the section name is valid

// then compare the string

if (section_name_valid (filedata, filedata->section_headers + i)

&& streq (section_name (filedata, filedata->section_headers + i),

name))

return filedata->section_headers + i;

return NULL;

}

You may also notice the reason for the no .dynamic section in the dynamic segment error message that we had in the previous chapter. Readelf loops through the sh_name field of each section entry, which is an offset into the String Table.

In our case,

sh_nameis null in all of our section entries, soreadelfcannot find it.

To find the string table, readelf loops through the entries of the dynamic table for an entry of type

DT_STRTAB. So no need to have a valid name here.

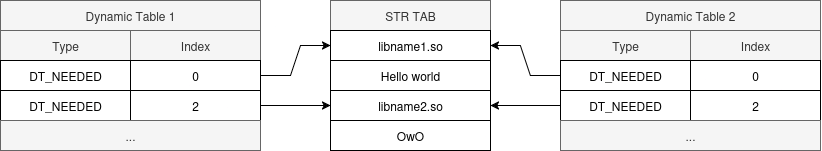

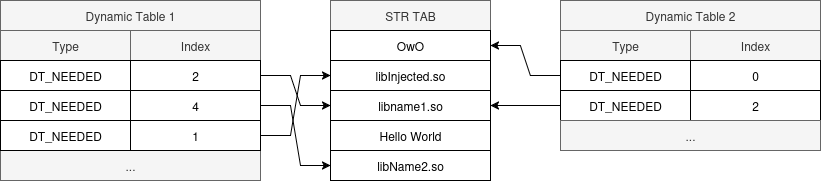

Here is a schema to help you understand:

LIEF internals

We now understand how readelf parses our binary. To understand what went wrong when injecting, we need to understand how the tool finds and parse the dynamic table.

ELF File parsing process

In this sub-chapter we will see how LIEF finds the Dynamic and String tables.

Luckily for us the code is well commented:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

template<class ELF_T>

ok_error_t Parser::parse_dyn_table(Segment& pt_dyn) {

// Parse the dynamic table. To process this table, we can either process

// the content of the PT_DYNAMIC segment or process the content of the PT_LOAD

// segment that wraps the dynamic table. The second approach should be

// preferred since it uses a more accurate representation.

// (c.f. samples `issue_dynamic_table.elf` provided by @lebr0nli)

...

const uint64_t dyn_start = pt_dyn.virtual_address();

const uint64_t dyn_end = dyn_start + pt_dyn.virtual_size();

const uint64_t load_start = segment->virtual_address();

const uint64_t load_end = load_start + segment->virtual_size();

The p_vaddr attribute of the PT_DYNAMIC segment entry is used to find the dynamic table. LIEF even goes further than this as they also compute the relative offset of the dynamic table based on the PT_LOAD segment entry that contains the dynamic table (source).

Note: If no wrapping

PT_LOADsegment entry is found, the parser falls back to reading directly from the file offset of thePT_DYNAMICsegment entry.

To confirm this we look at the output of our AppGuard binary:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

>>> bin = lief.ELF.parse("libAppGuard.so")

>>> for entry in bin.dynamic_entries:

... print(entry)

...

NEEDED : 0x00cd15 libandroid.so

NEEDED : 0x00cd23 liblog.so

NEEDED : 0x00cd2d libz.so

NEEDED : 0x00cd35 libm.so

NEEDED : 0x00ecc7 libdl.so

NEEDED : 0x00ecd0 libc.so

SONAME : 0x00ed0d libAppGuard.so

INIT_ARRAY : 0x0e5240 [0x2d620]

INIT_ARRAYSZ : 0x000008

FINI_ARRAY : 0x0e5248 [0x2d85c, 2d84c]

FINI_ARRAYSZ : 0x000010

HASH : 0x000228

GNU_HASH : 0x0029f8

STRTAB : 0x00e098

SYMTAB : 0x0052a8

STRSZ : 0x00ed21

SYMENT : 0x000018

PLTGOT : 0x0e8950

PLTRELSZ : 0x003810

PLTREL : 0x000007

JMPREL : 0x027888

RELA : 0x01d9d0

RELASZ : 0x009eb8

RELAENT : 0x000018

FLAGS : 0x000008 [BIND_NOW]

FLAGS_1 : 0x000001 [NOW]

VERNEED : 0x01d990

VERNEEDNUM : 0x000002

VERSYM : 0x01cdba

RELACOUNT : 0x000445

INIT : 0x108098

DT_NULL_ : 0x000000

Wait. Why is the table different from readelf ? I though both were reading from the segments (the plot thickens).

LIEF writing process

Here is what you need to know:

- The newly created dynamic table is written at the value of the

p_offsetheader of thePT_DYNAMICentry.

To sum up, LIEF recomputes the theorical virtual address of the dynamic table when parsing a file. But it does not do it while re-writing down the dynamic table (yes I should do a PR). The offset of the corresponding program header entry is used to write the table on the file.

Solving Problems

Double Dynamic Table

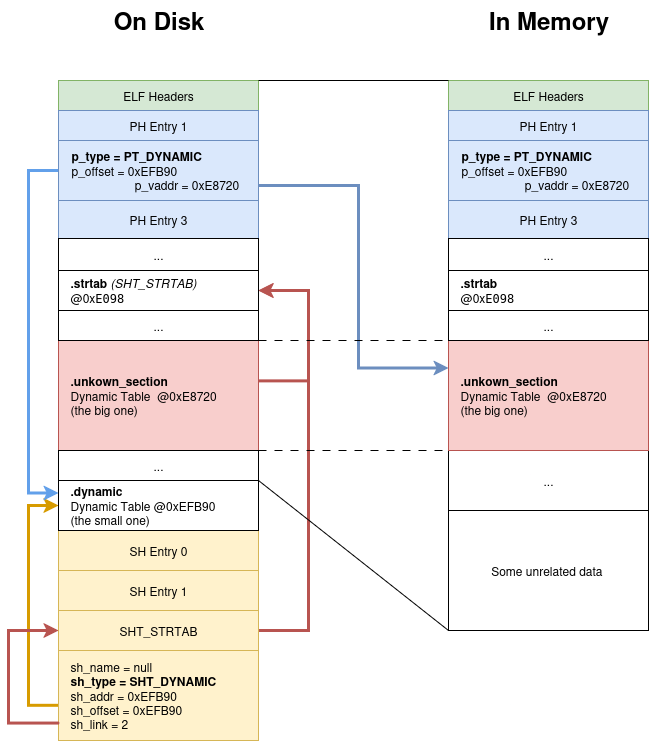

Let’s compare the SHT_DYNAMIC section header entry with the PT_DYNAMIC program header entry:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

PT_DYNAMIC

- p_vaddr = 0xE8720

- p_offset = 0xEFB90

SHT_DYN:

- sh_addr = 0xEFB90

- sh_offset = 0xEFB90

We observe that our dynamic table should be 0xEFB90 in our file and 0xE8720 in memory. But we also know (actually, I’m telling it to you right now) that the PT_LOAD program header are not mapping 0xEFB90 in memory…

We also know that 0xE8720 belongs to the second PT_LOAD segment that is mapped in memory with no particular offset. In other terms, what is at 0xE8720 in memory should be the same data that is at the offset 0xE8720 in our file.

Let’s do a double hexdump at the offset of the two tables.

The left part of the array corresponds to the type of the entry. The right part of the array is name of the entry referenced by an index in the string table.

If we open the file at 0xEFB90 we get:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

➜ hexdump -C -s 0xEFB90 ./libAppGuard.so -v | head

000efb90 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 15 cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000efba0 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 23 cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........#.......|

000efbb0 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 2d cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........-.......|

000efbc0 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 35 cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........5.......|

000efbd0 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 c7 ec 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000efbe0 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 d0 ec 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000efbf0 0e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 0d ed 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000efc00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000efc10 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000efc20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

If we open the file at 0xE8720 we get:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

➜ hexdump -C -s 0xE8720 ./libAppGuard.so | head

000e8720 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 15 cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000e8730 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 23 cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........#.......|

000e8740 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 2d cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........-.......|

000e8750 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 35 cd 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........5.......|

000e8760 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 c7 ec 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000e8770 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 d0 ec 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000e8780 0e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 0d ed 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000e8790 19 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 52 0e 00 00 00 00 00 |........@R......|

000e87a0 1b 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

000e87b0 1a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 48 52 0e 00 00 00 00 00 |........HR......|

There are two dynamic tables!

The first 7 entries are identical, but the second one has some more entries following.

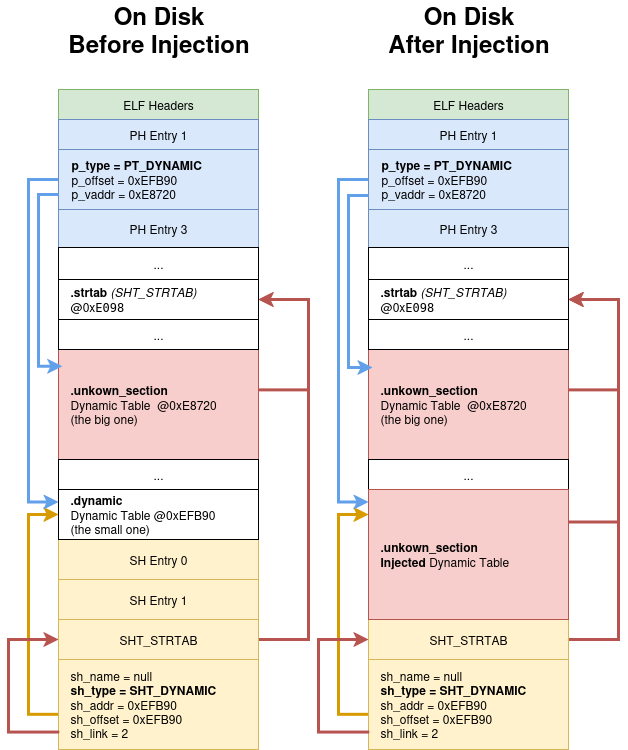

To help you understand the situation, I made an other schema of what our binary looks like on disk and in memory:

Notice how the dynamic table in the

.dynamicsection does not have any entry that points to the.strtab. Explaining why readelf can’t resolve the strings in the table.

So which one should we trust?

Choosing the right table

Since Sections should not be trusted and that PT_DYNAMIC is not used to map the file in memory. We can guess that p_offset (thus 0xEFB90) should be disregarded and p_vaddr = 0x0E8720 should therefore be the true dynamic table is*.

*Because the parent

PT_LOADsegment does not have any offset between the file offset and virtual addresses.

By editing the file and replacing the values of sh_addr, sh_offset and p_offset by 0xE8720, readelf can now correctly parse them !

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

➜ readelf -d libAppGuard_1E8720.so

readelf: Error: no .dynamic section in the dynamic segment

Dynamic section at offset 0xe8720 contains 32 entries:

Tag Type Name/Value

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libandroid.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [liblog.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libz.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libm.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libdl.so]

0x0000000000000001 (NEEDED) Shared library: [libc.so]

0x000000000000000e (SONAME) Library soname: [libAppGuard.so]

[Some more stuff]

Yippee dance ! But we’re not done yet.

One more important thing that is not shown above: the

0xEFB90(p_offset) table is outside of thePT_LOADranges: it is not loaded in memory.

Since our app is stuffed with anti-tampering protections, I want to make the minimal changes to confirm my hypothesis. I therefore tried to change the entry of a DT_NEEDED entry (in the big hidden dynamic table) to point for an other index on the string table (so I don’t have to update the string table).

So our binary should now display an error saying some random string could not be resolved as dependency.. Right ? Think again. The binary is loading as if I did not make any change.

To double check these results, I did the same operation on the .dynamic table (the small, not hidden but incomplete one) and did get an error message saying the library does not exists:

08-30 23:07:22.897 14646 14646 E AndroidRuntime: java.lang.UnsatisfiedLinkError: dlopen failed: library "_ZNSt6__ndk112basic_stringIcNS_11char_traitsIcEENS_9allocatorIcEEE9__grow_byEmmmmmm" not found: needed by /data/app/~~BP8uhydRMFp4NLuTHFofag==/dji.go.v5-aI75Kdn-FZIpSKTC8MxLiA==/lib/arm64/libAppGuard.so in namespace classloader-namespace

So both dynamic tables are actually used to link our binary ? …Yes 🥺👉👈.

To understand why, let’s look at the source code of the Android linker.

Android library loading process

I don’t fully understand how the linker deeply works. Take this part with a pinch of salt.

When you run System.LoadLibrary() it executes the following chain of calls: native_loader.OpenNativeLibrary() -> dlopen() -> __loader_dlopen() -> dlopen_ext() -> do_dlopen() -> find_library() -> find_libraries()

The find_libraries() function from the bionic linker works as follows:

1. LOADING PHASE

ELF files are mapped into memory and dependencies are discovered.

- The linker parses the main ELF file and creates a load task queue (

load_tasks), one perDT_NEEDEDlibrary.- Each

taskis anElfReaderwrapper that knows how tommapthe file, parse headers, and extract dynamic section info.

- Each

- The linker calls load_library() to run the tasks queued.

- Uses ElfReader::Read() to parse ELF headers, find

PT_LOADsegments, parse PT_DYNAMIC, etc.⚠️ It parses the

SHT_DYNAMICvalue, which must be equal to the p_offset and have the same size as in the program header.

TheSHT_STRTABis found viadynamic_shdr->sh_linkwhich is the index of theSHT_STRTABentry in theSHT.- Maps the segments into memory.

- Sets the value of

dynamic_pointer via theSHT_DYNAMICentry and strtab via theDT_STRTABentry.Later the linker will call the getter ElfReader::Dynamic() to get this data.

- Parses the dynamic section for recursive dependencies.

- Uses ElfReader::Read() to parse ELF headers, find

2. LINKING PHASE

- prelink_image():

- Processes relocations like

DT_HASH,DT_GNU_HASH,DT_INIT_ARRAYbased on thep_vaddrvalue of thePT_DYNAMICsegment ! - Also sets up

soinfo->strtab,soinfo->symtab,soinfo->plt_got, etc. based on thePT_DYNAMICdynamic table.⚠️ The entries

DT_HASH/DT_GNU_HASH,DT_SYMTABandDT_STRTABare actually required in thePT_DYNAMICDT for the lib to be loaded.

- Processes relocations like

- Calls into

soinfo->link_image()which actually does the linking job.

To sum up:

- Dependency resolving is done statically. The dynamic table is therefore read from the file.

- Linking is done in memory. The dynamic table is therefore read from the memory.

Answers

In readelf after injection, where do all these new dynamic entries come from?

LIEF parsed the correct dynamic entry. Upon modification it wrote the p_vaddr dynamic at the position of the p_offset of the PT_DYNAMIC entry. The two dynamic tables have a different size. The p_vaddr one was larger and overflowed into the section header table.

After injection, why does Ghidra show 6 DT_NEEDED tags but readelf show 7

Because Ghidra uses the p_vaddr of the PT_DYNAMIC entry to find the dynamic table whereas readelf uses the p_offset of the same structure. In our case, these values are different.

In the capture of the previous answer, in the “On Disk After Injection” table, Ghidra will read the non injected .unknown_section, whereas readelf will read the injected .unknown_section which is now referencing a string table.

Why does readelf show integers instead of names before the injection, but not after?

Because readelf loops through the segments to find the dynamic table (then sections, but not in our case). It finds the p_offset Dynamic Table which has no DT_STRTAB entry, thus fails to find the corresponding strings.

Why does Ghidra show incorrect library names after the injection, but not before?

Because Ghidra uses the dynamic table at the p_vaddr attribute of the PT_DYNAMIC entry. But LIEF wrote the injected dynamic table at the position of the p_offset one. In the process it changed the order of the entries in the string tables which led to incorrect string readings.

Here are two diagrams explaining the dynamic tables before and after injecting with LIEF. The first table is parsesd by LIEF, the second by Ghidra.

Why can’t readelf find the .dynamic section?

Because it searches for the section headers with the name .dynamic. In our case, all section names are stripped. It will therefore fallback the .dynamic section using the program headers.

Injecting the binary

I injected “libaaudio.so” into the binary. This lib is globally resolved so I don’t have to add libs in the APK. Yet, the APK still does not work.

With adb logcat we get:

1

08-26 20:51:23.986 14508 14508 E AndroidRuntime: java.lang.UnsatisfiedLinkError: dlopen failed: "/data/app/~~XPXwMp_0y7Lf8OsXWPEG8g==/dji.go.v5-23_e4w2buLG8LqG2P51N5g==/lib/arm64/libAppGuard.so" .dynamic section has invalid size: 0x230, expected to match PT_DYNAMIC filesz: 0x210

It can be quickly fixed by patching the segment size in the PHT to 0x230. I kinda expected this to happen.

The app now starts but eventually stops after a few seconds. It does run for longer than what I got using frida. So I think this should be enough time to dump the dex classes.

I eventually found that I did not have to repack the APK in order to edit a native lib. With a rooted phone, one may directly push them into the app directory on the phone. This solved the crash which I assume to be an anti-tampering technique against repacking.

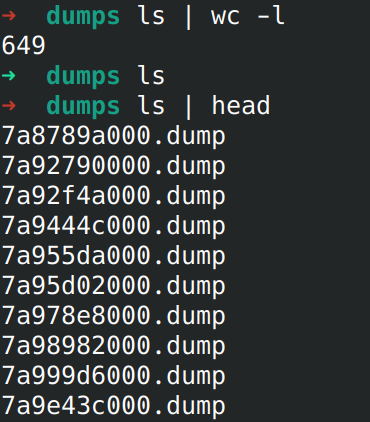

In order to dump the dex files I (aka ChatGPT) wrote a lib file that sleeps for 5 seconds, then parses the /proc/self/maps entries in order to dump the memory locally.

You may find the scripts on my NativUwU repo.

Here is a summary of what the injected lib (libcaca.so) does:

- Sleeps for 5 seconds

- Fetches the

/proc/self/mapsfile and writeit in quoicoubeh.txt. - For each entry of the mapped memomry and if it is readable, it will dump it in the

/data/data/dji.go.v5/files/dumpsfile.

This article is already too long, the exact reproduction steps are on the repo.

We now have about a gigabyte of binary blob to parse in order to find the dex files.

Finding the dex files

Luckily, finding and extracting the Dex files is pretty simple. It has dex as magic byte and a fix offset (0x20) indicating the length of the dex file.

So I (once again, ChatGPT) wrote a quick python script do extract dex files from a dump, which worked pretty well. You may also find it on my git.

To avoid dumping dex files from a gig of memory, a simple grep DJIAccountAuthenticator * was enough to find the memory segment that we wanted.

Quick tip: There is an option to ignore the verification of the dex files checksum.

And voila, I now have the unpacked, half corrupted, Java classes running on the Android app !

Restrospective

Simply knowing how the ELF format works is not enough when getting confronted with some actual obfuscated binaries. A deep understanding of how ELF files are parsed by various Linux processes is also important.

Actually you may achieve the same results with lief without patching the binary prior to injection. I did miss the invalid section size issue in the adb logcat output that also occurs when injecting the original binary.

The linker requires the p_offset of the PT_DYNAMIC to match the sh_offset of the SHT_DYNAMIC. Hence why there are two different values in the PT_DYNAMIC (source).

readelf reads the sections table to find the dynamic table. If the .dynamic section is not found, it assumes that it is where PT_DYNAMIC points to.

DT_NEEDED entries are parsed from the sections (kind of) ! In Android, the .dynamic section entry must have the same offset and size of the PT_DYNAMIC p_offset entry. A DT_STRTAB is not required as it is found via the sh_link attribute of the SHT_DYNAMIC.

As a final word:

I injected libAppGuard to dump from memory. But was it really necessary ? Any other lib could have been used to read the process memory and dump it locally.

More reading

- https://www.virusbulletin.com/uploads/pdf/conference/vb2024/papers/Detecting-Shared-Object-injection.pdf

- https://zhenhuaw.me/blog/2016/android-dynamic-linker.html